Ah, the breakfast cereal- a classic food that is probably the most common of pantry foods among households. Do you ever open a new box of cereal, pour it in with your milk, and take a bite, enjoying the sweet crunchiness? The cereal has gone through special treatment and preservation to make it to your morning bowl, and most of us don’t give it much thought because we tend to finish our boxes of cereal in a few days before we can ever see what “spoiled” cereal looks, tastes, and smells like- but it exists! Cereal can go bad, and that’s exactly why we’re here.

Cereal grains from which cereal is eventually produced are very susceptible to microbiological and environmental damages. Bacteria love to frequent cereal grains and contaminate them only to use them for proliferation. The perfect conditions for bacteria to grow in must be highly moist (have a high water activity) at equilibrium and must have a high humidity. The bacteria actually can do no damage until the grain is stored in aerobic conditions- until then, the bacteria are kept at bay by the plant’s cell walls. So naturally, a very important preservation method to consider is drying the cereal grains to a moisture level less than 14% and a temperature of less than 15 degrees Celsius. Yeasts also can carry on from the raw, unprocessed grain to the processed food and cause degradation there. But molds are the most damaging to the grain, causing more degradation than any bacteria living on the surface.

The two groups of fungi that can affect cereal grains are field fungi and storage fungi. Field fungi invade grain in the field when the grain is high in moisture (18 to 30%, i.e., at high aw) and at high relative humidities (90 to 100%). Storage fungi invade grain in storage at lower moisture contents (14 to 16%), lower aw and lower relative humidities (65 to 90%). To prevent spoilage by storage fungi, the moisture content of starchy cereal grains should be below 14.0%. As with any mold that grows on food, the most noticeable effects of deterioration are discoloration, development of visible mold growth, and musty or sour odors. But we must examine the possibility of the development of mycotoxins, and how they can be reduced.

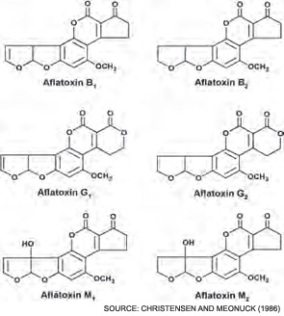

A study in 2006 took 349 breakfast and infant cereal samples from 2002 to 2005 to test for aflatoxins (a form of mycotoxin). Chemically, aflatoxins look like this:

The results of the study showed that levels of aflatoxins in the surveyed cereals were almost significant, matching the exact maximum amount of toxins present in food as given by the European union.

Aflatoxins are classified in two broad groups according to their chemical structure; they display potency of toxicity, carcinogenicity, mutagenicity. Structurally the dihydrofuran moiety, containing double bond, and the constituents linked to the coumarin moiety are of importance in producing biological effects.

The aflatoxins fluoresce strongly in ultraviolet light; B1 and B2 produce a blue fluorescence where as G1 and G2 produce green fluorescence.To test grains for mycotoxins (and subsequently aflatoxins, various detection methods, such as fluorescence, ultraviolet absorption, and others have been combined with chromatographic methods to be used. New methods based on the production of antibodies specific for individual mycotoxins have also been developed and include enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays and immunoaffinity columns. By detecting potential toxins before packaging and distributing, many future problems are spared.

Another very important method of assuring safe cereal grain and long preservation of cereal is mixing the grain with certain acids- in most cases, it is propionic acid. Propionic treatment will enable grain up to 30% moisture content to be safely stored. Without propionic acid, the grains depend on the reduction of lactic acid fermentation and lowering pH. Propionic acid works for the same purpose, but much more quickly- just 1% of propionic acid in high moisture grains completely inhibits aflatoxin development.

Although we don’t notice it because of its commonplace in our homes, cereal has to go through a very exact process of preservation, beginning from the grain, to ensure that it can safely travel to factories to be manufactured into the flavors and shapes we know today in our favorite cereal boxes. If it weren’t for these methods, we might still be eating cereal- but it would probably kill us.